| VIVO Pathophysiology | The Small Intestine |

Absorption of Minerals and Metals

The vast bulk of mineral absorption occurs in the small intestine. The best-studied mechanisms of absorption are clearly for calcium and iron, deficiencies of which are significant health problems throughout the world.

Minerals are clearly required for health, but most also are quite toxic when present at higher than normal concentrations. Thus, there is a physiologic challenge of supporting efficient but limited absorption. In many cases intestinal absorption is a key regulatory step in mineral homeostasis.

Calcium

Calcium is absorbed from the intestinal luman by two distinct mechanims, and their relative magnitude of importance is determined by the amount of free calcium available for absorption:

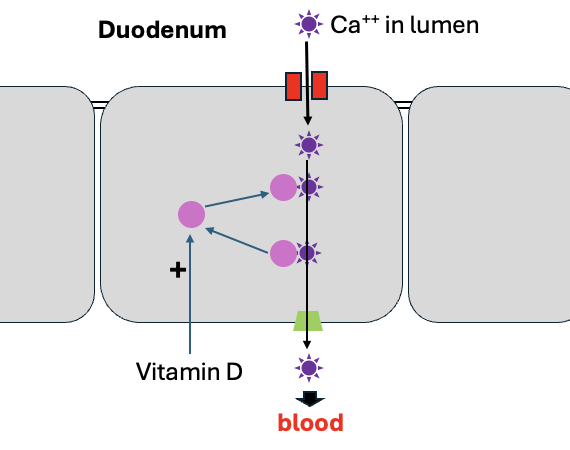

1. Active, transcellular absorption occurs only in the duodenum when calcium intake is low. This process involves import of calcium into the enterocyte, transport across the cell, and export into extracellular fluid and blood. Calcium enters the intestinal epithelial cells through voltage-insensitive (TRP) channels and is pumped out of the cell via a calcium-ATPase.

The rate limiting step in transcellular calcium absorption is transport across the epithelial cell, which is greatly enhanced by the carrier protein calbindin, the synthesis of which is totally dependent on vitamin D.

2. Passive, paracellular absorption occurs in the jejunum and ileum, and, to a much lesser extent, in the colon when dietary calcium levels are moderate or high. In this case, ionized calcium diffuses through tight junctions into the basolateral spaces around enterocytes, and hence into blood. When calcium availability is high, this pathway responsible for the bulk of calcium absorption, due to the very short time available for active transport in the duodenum.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus is predominantly absorbed as inorganic phosphate in the upper small intestine. Phosphate is transported into the epithelial cells by contransport with sodium, and expression of this (or these) transporters is enhanced by vitamin D.

Iron

Iron homeostasis is regulated at the level of intestinal absorption, and it is important that adequate but not excessive quantities of iron be absorbed from the diet. Inadequate absorption can lead to iron-deficiency disorders such as anemia. On the other hand, excessive iron is toxic because mammals do not have a physiologic pathway for its elimination.

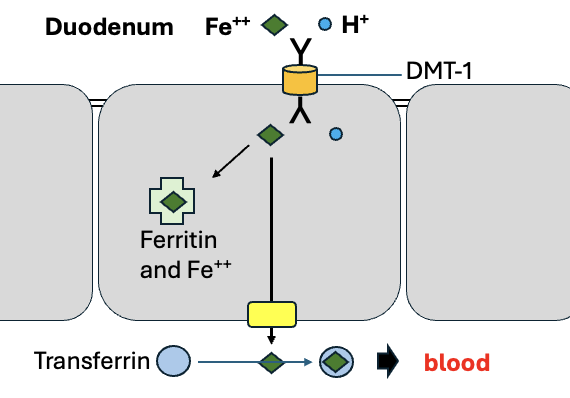

Iron is absorbed by villus enterocytes in the proximal duodenum. Efficient absorption requires an acidic environment, and antacids or other conditions that interfere with gastric acid secretion can interfere with iron absorption.

Ferric iron (Fe+++) in the duodenal lumen is reduced to its ferrous form through the action of a brush border ferrireductase. Iron is the cotransported with a proton into the enterocyte via the divalent metal transporter DMT-1. This transporter is not specific for iron, and also transports many divalent metal ions.

Once inside the enterocyte, iron follows one of two major pathways. Which path is taken depends on a complex programming of the cell based on both dietary and systemic iron loads:

- Iron abundance states: iron within the enterocyte is trapped by incorporation into ferritin and hence, not transported into blood. When the enterocyte dies and is shed, this iron is lost.

- Iron limiting states: iron is exported out of the enterocyte via a transporter (ferroportin) located in the basolateral membrane. It then binds to the iron-carrier transferrin for transport throughout the body.

Iron in the form of heme, from ingestion of hemoglobin or myoglobin, is also readily absorbed. In this case, it appears that intact heme is take up by the small intestinal enterocyte by endocytosis. Once inside the enterocyte, iron is liberated and essentially follows the same pathway for export as absorbed inorganic iron. Some heme may be transported intact into the circulation.

Copper

Dietary copper is absorbed predominantly in the duodenum and jejunum by two processes: a rapid, low capacity system and a slower, high capacity system, which are similar to the two processes seen with calcium absorption. Cu++ is converted to Cu+ and then absorbed into the epithelial cella through the copper transporter 1 (Ctr1); it is subsequently exported into blood by an ATPase cotransporter. Inactivating mutations in the gene encoding an intracellular copper ATPase have been shown responsible for the failure of intestinal copper absorption in Menkes disease.

A number of dietary factors have been shown to influence copper absorption. For example, excessive dietary intake of either zinc or molybdenum can induce secondary copper deficiency states.

Zinc

Zinc homeostasis is largely regulated by its uptake and loss through the small intestine. Although a number of zinc transporters and binding proteins have been identified in villus epithelial cells, a detailed picture of the molecules involved in zinc absorption is not yet in hand.

Intestinal excretion of zinc occurs via shedding of epithelial cells and in pancreatic and biliary secretions.

A number of nutritional factors have been identified that modulate zinc absorption. Certain animal proteins in the diet enhance zinc absorption. Phytates from dietary plant material (including cereal grains, corn, rice) chelate zinc and inhibit its absorption. Subsistance on phytate-rich diets is thought responsible for a considerable fraction of human zinc deficiencies.

References and Reviews

- Andrews NC, et al. Disorders of iron metabolism. New Eng J Med 341:1986, 1999.

- Bronner F, et al. Calcium absorption: A paraadigm for mineral absorption. J Nutrition 128:917-920, 1998.

- Krebs NF, et al. Overview of zinc absorption and excretion in the human gastrointestinal tract. J Nutrition 130:1374S-1377S, 2000.

- Kuanal RC, et al. Nemere I: Regulation of intestinal calcium transport. Annu Rev Nutr 28:179-196, 2008.

- Lonnerdal B, et al. Dietary factors influencing zinc absorption. J Nutrition 130:1378S-1385S, 2000.

- Miret S, et al. Physiology and molecular biology of iron absorption. Ann Rev Nutr 23:283-301, 2003.

- Wessling-Resnick M, et al. Iron transport. Annu Rev Nutr 20:129-151, 2000.

Small Intestine: Introduction and Index Small Intestine: Introduction and Index |

Updated December, 2025. Send comments to Richard.Bowen@colostate.edu