| Reproduction Index | Glossary |

|---|

|

Placentation in Dogs and Cats |

Dogs and cats are well-known members of the group of species that have zonary placentae. Other examples of animals with this type of placentation include mustelids (ferrets, skunks), bears, seals and elephants. ImplantationDogs and cats are litterbearing species, and prior to fixation and implantation, the blastocysts become evenly spaced throughout the uterine horns. In both species, there appears to be efficient transuterine migration. In dogs, implantation occurs roughly 18 to 20 days after the preovulatory LH surge (about diestrus day 8 to 10). In cats, implantation has been reported to occur 12 to 14 days after mating. Implantation is centric and antimesometrial. Gross Structure of the PlacentaThe zonary placenta takes the form of a band that encircles the fetus. In dogs and cats, it is complete, while in species like ferrets and raccoons, it is incomplete (i.e. two half bands). The images below show dissection of a near-term cat uterus removed surgically for population control: |

|

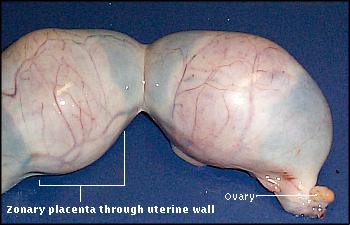

Cats typically have 3 to 8 fetuses. It is not unusual for one or more to die in utero and the others survive to be born. This image shows the end of one uterine horn. The zonary placentae of two fetuses are clearly visible through the uterine wall. |

|

|

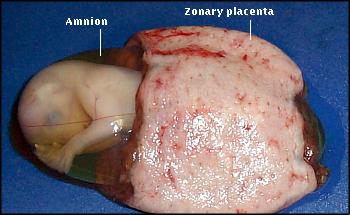

Dissecting the uterus away from the conceptuses reveals the chorioallantois as an ovoid structure modified circumferentially to form the zonary placenta. |

|

|

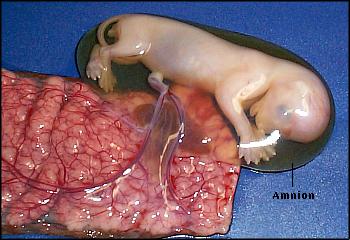

In this image, the chorioallantois has been dissected away to show the fetus, encased in its amnion. |

|

|

When the placenta is opened up, its rich vasculature and the umbilical vessels of the fetus are evident. (Note: the amniotic fluid is crystal clear, but looks dark due to the background.) |

|

|

To better appreciate the relationships between uterus, placenta and fetus, examine the 3D model of a segment of a pregnant cat uterus shown below. In the left image, the uterus (green) surrounds the conceptus. In the middle image, the uterus is transparent, and the fetus (tan) and placenta (red) are visible. In the right image, the fetus and uterus have been removed, showing the placenta. These images are stereo pairs and will look blurred if viewed with the naked eye - try using a pair of stereo glasses.  The canine placenta looks very similar to that of cats. A feature usually seen in the placentae of both species is marginal hematomas (hematophagus zones). These are bands of maternal hemorrhage at the margins of the zonary placenta. The products of hemoglobin breakdown give them a distinctly green coloration in dogs, whereas in cats they are brownish and usually less obvious. Microscopic Structure of the PlacentaDogs and cats have an endotheliochorial type of placenta. In this type of placenta, the endometrial epithelium under the placenta does not survive implantation, and fetal chorionic epithelial cells come to be in contact with maternal endothelial cells. During implantation, cytotrophoblast cells surrounding the central third of the chorioallantois proliferate to form a syncytium called syncytiotrophoblast. The syncytiotrophoblast erodes through the endometrial epithelium and flows around maternal capillaries. Initially, the invading fetal cells are in the form of villi, but villi soon coalesce to form a labyrinthine-type of placenta. Placental EndocrinologyConcentrations of reproductive hormones in systemic blood of pregnant dogs and cats have been reported by several investigators. However, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the source of these hormones, that is, precisely what contribution is made the the corpora lutea versus the fetoplacental unit. The canine placenta is said to produce little if any quantity of steroid hormones. As with other species, maintainance of pregnancy is dependent on continued secretion of progesterone during gestation, but corpora lutea appear to be the exclusive source of progesterone in the bitch. Luteal secretion of progesterone is, in turn, dependent on secretion of luteinizing hormone and probably prolactin from the anterior pituitary. Removal of the ovaries at any time during canine gestation leads to termination of the pregnancy. Also, progesterone profiles in pregnant and pseudopregnant bitches are indistinguishable until late in gestation or diestrus. In cats, serum progesterone concentrations are similar in pregnant and pseudopregnant animals for roughly the first 3 weeks after ovulation. After that time, progesterone concentrations decline in pseudopregnant cats, but increase in pregnant cats. It is not known with certainty whether this elevation of progesterone in pregnancy reflects placental synthesis or enhanced luteal synthesis. Apparently, the ovaries can be removed after about day 45 in cats without interupting the pregnancy, which might suggest that the placenta can indeed synthesize progesterone.

Both dogs and cats produce the hormone relaxin during pregnancy. In pregnant bitches, relaxin is first detected in serum about 4 weeks into gestation, and increases substantially during the remainder of gestation. The placenta is known to be the primary site of secretion of relaxin in dogs, although a smaller contribution is made by the ovaries and luteal synthesis of relaxin persists for several weeks after parturation. Relaxin is not present in serum of pseudopregnant bitches, and thus can be reliably used as a pregnancy test. The cat placenta also produces copious quantities of relaxin, beginning about 20 days of gestation. As with dogs, relaxin has not been detected in the serum of cycling or pseudopregnant cats. Neither dogs nor cats produce a chorionic gonadotropin.

|

| Index of: Implantation and Development of the Placenta |

Last updated on March 26, 2001 |

| Author: R. Bowen |

| Send comments via form or email to rbowen@colostate.edu |